Glazeware artist firing new life into craft

Updated: 2024-07-23

Local inheritor in Shanxi brings modern innovations to ancient production techniques

The deft hands of a master craftsman can breathe life into a piece of clay and firing it in high-temperatures can make that life eternal – that's what a master of glazeware in Shanxi province believes about this ancient art with a history of more than 1,000 years.

In Mazhuang Shantou village in Yingze district, Taiyuan, Su Yongjun busies himself every day designing and making glazeware items, and teaching apprentices in his studio called the "Shantou Kiln Site".

Su is the eighth-generation inheritor of Su's Glazeware, a local school of glazeware made with techniques passed down from the ancestors of the Su family for hundreds of years.

Although he is the recognized eighth generation in this family-run business, Su said the family tradition in making glazeware dates back about half a millennium. And he pointed out that the glazeware industry in Shanxi has an even longer history, with records pointing to the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-543).

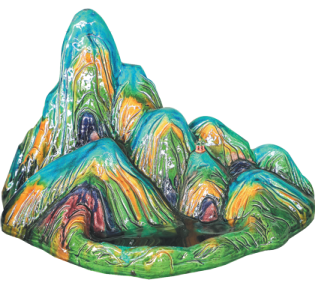

Glazeware, or glazed pottery featuring a shiny, colorful surface, is called liuli in Chinese. It is widely used in the construction industry as glazed tiles, rooftop decorations and screen walls in the residences of the royal family, the noble and rich, according to Su.

"The industry in Shanxi began in the Northern Wei Dynasty," Su said. "It reached its peak of development in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), and this was when the Su family started to engage in the trade."

He explained that when his family members were building new kilns on an old site, they found a pottery mold with inscriptions of the family name "Su" and the year it was made. "That relic shows that our family business can date back to more than 500 years ago."

Su said there were four families in Shanxi known for their glazeware production business, and Su was one of them.

"According to historical records, the Zhao family – one of the top four – moved to Beijing in the middle of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911)," Su said. "The family's business grew rapidly in the city and became a major supplier of glazed tiles to the Forbidden City and royal gardens."

As the demand for glazed tiles and other glazeware items from the royal family had far surpassed the supply, some Zhao family members requested that the Su family join in their business.

Since then, the Su family began to deliver their locally made glazed tiles to Beijing and they later built kilns in Beijing and fired the tiles there. "That was the heyday of our family business," Su said. "And the business is still kept to this date."

In his Shantou Kiln Site studio, Su explained the secret behind the sustained business.

He picked up a piece of black clay, saying: "The selection of raw materials is crucial for glazeware production.

"This is a kind of clay with a low content of aluminum. It features strong malleability and can help to keep a stable shape for the fired item in high temperatures."

He added that one unique technique in glazing is the use of wheat flour and vinegar, which can help to sustain the glaze colors.

"We also have unique formulas in making colored glaze," Su said. "For instance, we developed the 'Royal Yellow' glaze for the royal family and this was something other suppliers could not duplicate."

He added that the three glaze colors known as "peacock blue", "peacock green" and "peacock purple" were the most popular in the market a century ago. "But unfortunately the formulas for the three colors were lost for some unknown reasons," Su said.

He said since his grandfather, his family members have made great efforts to rescue the lost formulas and the endeavors paid off in recent years.

"By referring to our family's documents and collaborating with other glazeware masters outside our family, we successfully retrieved the formula for peacock blue," Su said, adding that they are now capable of producing dozens of glazeware varieties featuring peacock blue.

The glazeware production technique of the Su family was recognized as a national intangible cultural heritage item in 2008.

In addition to inheritance, Su said innovation is also crucial for passing down and developing this centuries-old art.

One innovative move is that Su and his colleagues are using electricity and natural gas to fire glazeware items. "Compared with the traditional firing technique using coal or timber, we found electric or gas firing can lead to greater stability and efficiency," he said.

Apart from glazed tiles and other construction components, Su has also extended the industry to new fields like artifacts, tea sets and stationery.

Su is also promoting the craft to the wider society. He and his family members are now operating a workshop for people from across Shanxi and the country to learn more about this form of art.

Xue Lin contributed to this story.

A glazeware elephant statue made at the studio of the Su family. CHINA DAILY

A glazeware artifact depicting a stylized landscape. CHINA DAILY

Su Yongjun (center) holds a training session on glazeware making at his studio. CHINA DAILY